By Emma Seppala on Mon, Dec 16, 2019

Why are we always exhausted at the end of a workday? Why do we come home wiped out, with barely enough energy to make dinner before collapsing for the night?

Normally, when we think about being tired, we think of physical reasons: lack of sleep, intense exercise, or long days of physical labor. And yet, as Elliot Berkman, professor of psychology at the University of Oregon, pointed out to me in an interview, in our day and age, when few of us have physically demanding jobs, we are wiping ourselves out through psychological factors. Yet as Carl Lewis, Gold Medalist and author of Inside Track points out – channeling your energy is everything – how can we maximize it?

After all, the physical effort we exert in our day jobs does not warrant the fatigue we experience when we get home. If you are a construction worker, a farmer toiling in a field, or a medical resident working both day and night shifts, then yes, physical exhaustion might be the reason for your fatigue. But otherwise, Berkman points out, your fatigue is mostly psychological. “Does your body get tired until you really can’t do anything at all?” asks Berkman. “Actually, it would take a long time to get to that point of complete physical exhaustion.”

One of the main reasons for our mental exhaustion is high-intensity emotions.

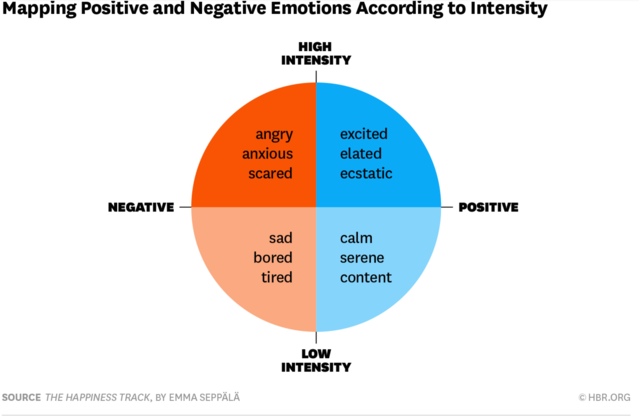

One way psychologists distinguish emotions is along two dimensions: positive/negative and high intensity/low intensity. In other words, is the emotion positive (like elated or serene) or negative (like angry or sad)? And is it high intensity (like elated or angry) or low intensity (like serene or sad)?

It’s easy to see how high-intensity negative emotions might wear us out during the course of the day — and not just frustration and anger. Many of us have come to rely on our stress response to get things done. We fuel ourselves up with adrenaline and caffeine, over-scheduling ourselves and waiting until the very last minute to complete projects, waiting for that “fight or flight” mode to kick in and believing we need a certain amount of stress to be productive.

But high-intensity positive emotions can also be taxing. And research shows that we — especially Westerners, and Americans in particular — thrive on high-intensity positive emotions. Research by Jeanne Tsai of Stanford University, with whom I conducted several studies, shows that when you ask Americans how they would ideally like to feel, they are more likely to cite high-intensity positive emotions like elated and euphoric than low-intensity positive emotions like relaxed or content. In other words, Americans equate happiness with high intensity. East Asian cultures, on the other hand, value low-intensity positive emotions like serenity and peacefulness.

When Jeanne and I ran a study to figure out why Americans value high-intensity positive emotions, we found that Americans believe they need high-intensity emotions to succeed — especially to lead or influence. In a study we ran, for example, people wanted to feel high-intensity positive emotions like excitement when they were in a role that involved leading or trying to influence another person. This intensity is reflected in the language we use to discuss achievement goals: we get fired up, pumped, or amped up so that we can bowl people over, crush projects, or crank out presentations — these expressions all imply that we need to be in some kind of intense attack mode. Go get it, knock it out of the park, and muscle through.

The problem, however, is that high-intensity emotions are physiologically taxing. Excitement, even when it is fun, involves what psychologists call “physiological arousal” — activation of our sympathetic (fight-or-flight) system. High-intensity positive emotions involve some of the same physiological responses as high-intensity negative emotions like anxiety or anger. Our heart rate increases, our sweat glands activate, and we startle easily. Because it activates the body’s stress response, excitement can deplete our system when sustained over longer periods — chronic stress compromises our immunity, memory, and attention span. In other words, high intensity — whether it’s from negative states like anxiety or positive states like excitement — taxes the body.

High-intensity emotions are also mentally taxing. It’s hard to focus when we’re physiologically aroused and overstimulated. We know from brain-imaging research that when we’re feeling intense emotions, the amygdala is activated – that’s the same region that lights up when we’re feeling a fight-or-flight response. We need to use effort and emotion-regulation strategies from a different part of our brain, located in the prefrontal cortex, to calm ourselves enough to get our work done. This emotion regulation itself requires additional effort.

The result? You tire easily. Whether you’re getting amped up with anxiety or with excitement, you are draining yourself of your most important resource: energy. That’s why I devote a whole chapter of my book The Happiness Track to energy management – energy is the one resource we should be attending to daily. If we don’t have energy, we can’t do anything – whether that’s working, parenting, or attending to our other responsibilities.

Excitement, of course, can be a positive emotion and it certainly feels a lot better than stress. But just as a sugar high may feel great for a while, it sends your body into a physiological high that can end with a crash. You are bound to feel tired sooner than if you had remained in a calm state.

This isn’t to say you should never feel stressed or excited — nor should you lose your enthusiasm for your work. However, I’m suggesting you make more time for calm activities in your life and learn to tap into that other side of your nervous system — the parasympathetic “rest and digest” side, that helps restore your health and your well-being, making you more resilient over the long run. Doing so will help you save your energy for when you need it most.

comments