By Emma Seppala on Mon, Apr 20, 2020

In workplaces and families across the world, communication has gone online. We send endless emails; we video chat rather than travel across town to meet. Actually sitting down and interacting with someone in person can seem like a rare luxury.

But as technology spreads, are we losing our ability to connect and empathize with others—and with it, the happiness and success that empathy brings? How can compassion happen if face-to-face time is slowly disappearing?

Empathy is the ability to "resonate" with another person: to feel their emotions and understand their perspective. Research on empathy has emphasized our keen ability to literally read others: By mirroring or subtly mimicking their facial expressions, we understand what they are experiencing. If we see someone cry, we may feel our eyes water; if we see them frown, we do the same, Swedish research demonstrates. (In fact, if you get Botox between your eyebrows and are unable to mirror someone’s frown, your ability to rapidly interpret their emotions may be impacted, one study showed).

Luckily, though, empathy relies on more than reading facial expressions. In fact, new research is suggesting just how powerful the voice can be to help us connect, and it’s good news for our technological lifestyle.

Listening for empathy

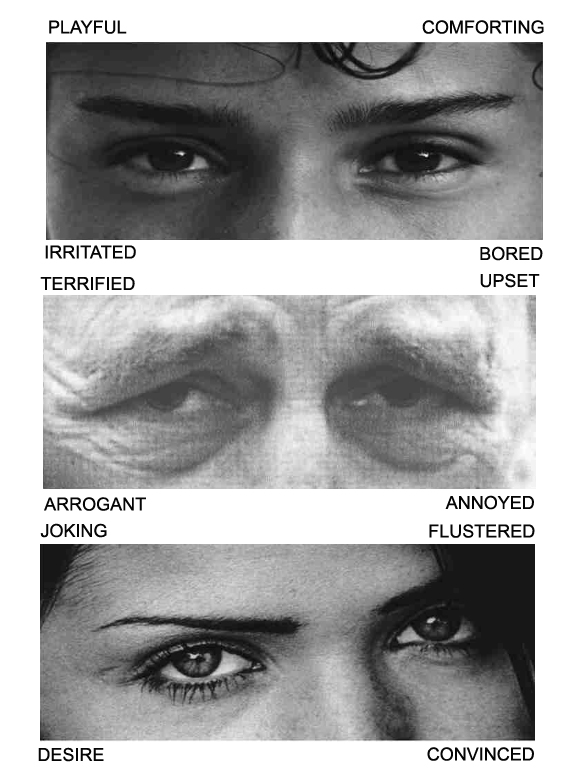

The way we usually try to identify other people’s emotions is through their facial expressions—their eyes in particular. We are told that “the eyes are the windows to the soul,” and eye contact is certainly critical in empathy. Many psychologists use the Reading the Mind in the Eyes exercise to test empathy for their experiments. The idea is that, if you can detect the subtle shifts in the looks people give you, you can understand what they are feeling and respond appropriately.

But a new study by Michael Kraus of the Yale University School of Management has found that our sense of hearing may be even stronger than our sight when it comes to accurately detecting emotion. Kraus found that we are more accurate when we hear someone’s voice than when we look only at their facial expressions, or see their face and hear their voice. In other words, you may be able to sense someone’s emotional state even better over the phone than in person.

In one experiment, Kraus asked participants to watch videos of two people interacting and teasing each other, then to rate how much the two actors felt a range of different emotions during the interaction. In another study, participants had conversations on camera about film, television, food, and beverages, in a room that was either lit or pitch dark. In a third study, a different set of participants were asked to rate the emotions of the conversations partners who had been videotaped. In all these cases, the participants were most accurate at identifying others’ emotions when they only heard people’s voices (compared to when they looked at facial expressions alone, or looked at facial expressions and heard voices). A few more experiments yielded similar results.

In several follow-up studies, Kraus honed in on the reason why the voice—especially when it is the only cue—is such a powerful mode of empathy. He asked participants to discuss a difficult work situation over a video conferencing platform (Zoom) using either just the microphone or the microphone and the video. Once again, participants were more accurate at detecting each others’ emotions in voice-only calls. When we only listen to voice, he found, our attention for the subtleties in vocal tone increases. We simply focus more on the nuances we hear in the way speakers express themselves.

When you are speaking to someone on the phone, for example, you might be more likely to notice if they are breathing quickly and appear nervous, or if their speech is monotone and they sound down or tired. On the other hand, you can easily detect enthusiasm and excitement when someone speaks in a high-pitched and rapid manner.

So how can we get better at interpreting emotions in the voices of our coworkers and loved ones? There isn’t much research to date exploring this question specifically. One study on infant cries suggested that parents with more musical training were better at distinguishing distress cries from other types of cries. But, really, we might not need much training. Kraus found that, once you remove other inputs (like facial expressions), your attention naturally sharpens and hones in on vocal cues.

The power of the voice

Given that we often try to understand other people’s emotions by relying on their faces (and, in fact, tend to overestimate our ability to do so), Kraus’s study is a wake-up call. The voice may be a far more reliable predictor than the face, especially if we can devote our complete attention to it.

Previous research has shown just how much information the voice can convey. Research led by the Greater Good Science Center’s Emiliana Simon-Thomas and Dacher Keltner shows that we don’t only detect basic emotional tone in the voice (e.g., positive vs. negative feelings or excitement vs. calm); we are actually capable of detecting fine nuances. We can distinguish anger from fear and sadness; awe from compassion, interest, and embarrassment. Many of the “vocal bursts” that signify emotion—from the ahhh! of fright to the ahhh of pleasure—are recognizable across cultures.

The human ability to perceive nuances in voices is extremely sophisticated, research shows. It may have offered a strong evolutionary advantage, helping our ancestors distinguish familiar from unfamiliar voices, and perceive expressions of need and distress that helped ensure survival. Think of the visceral reaction we have towards a baby crying: Mothers are even more attuned to their own baby’s cry, especially if they have given natural birth.

In fact, vocal emotion recognition even has a separate brain region from facial recognition of emotion, a brain-imaging study found. When two people talk and truly understand each other, another brain-imaging study suggested, something quite spectacular happens: Their brains literally synchronize. It is as if they are dancing in parallel, the listener’s brain activity mirroring that of the speaker with a short delay. That is the kind of communication we should all aim for—and one that may lead to not only better relationships, but more compassion.

What we now need is more research on how empathy works in text-only messaging. One of our foremost modes of communication at the moment is arguably the smartphone—from texting to messaging on Facebook or WhatsApp —and it may be much more challenging to detect emotions accurately in short texts than in voices or facial expressions (emoticons or not).

Meanwhile, perhaps we can be less concerned about the trend toward more phone calls and fewer face-to-face interactions at work and in our personal lives. And perhaps, especially when we are having a difficult conversation that necessitates a lot of empathy, we should opt for a phone call over a FaceTime or Skype call. As counterintuitive as it seems, we may be more attuned to a conversation partner’s emotions through their voice.

comments